This story is part of a week-long SPACE.com series on what it would take for humanity to return to the moon to stay. Coming on Monday: 21st Century Moon bases and the new moon race.

Companies hoping to mine the moon's huge stores of water ice can likely do so legally, experts say, though firms may want to hold off until new legislation grants them explicit title over whatever lunar muck they dredge up.

The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 seems to permit extractive activities on the moon and other celestial bodies, according to space-law experts. But it's not entirely clear that mining companies would own the stuff that they extract. That fuzziness could be a problem for outfits contemplating a moon mining endeavor, which could have initial costs running into the tens of billions of dollars.

"As far as title goes, it's a gray area," international lawyer and space-law expert Timothy Nelson, who works for the firm Skadden in New York City, told SPACE.com. "And from a risk perspective, lack of clarity means it doesn't exist." [Q & A: One Company's Moon Mining Plan]

Water on the moon: An abundant resource

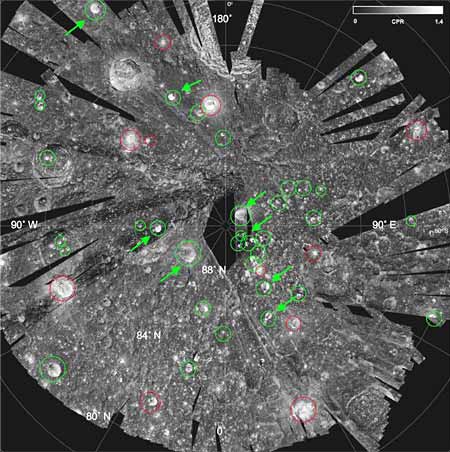

The moon has a lot of water ice, as recent discoveries have made clear. Frigid craters at both lunar poles have likely been trapping and accumulating water for billions of years — water that is relatively pure and easy to get at.

Scientists and entrepreneurs alike have begun talking seriously about mining this ice, and not just to keep future moon dwellers hydrated. Water ice can also be separated into its constituent hydrogen and oxygen — the chief components of rocket fuel.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Propellant could be produced from moon water and sold at refueling stations in low-Earth orbit, allowing spaceships and satellites to top off their tanks in space. This arrangement could help spur a wave of trade, travel and exploration throughout the solar system, researchers and businessmen have argued.

It would make more economic sense to supply the filling stations from the moon, they've added. The moon's gravity is just one-sixth that of Earth’s, so launching from there is far cheaper.

Some companies are already drawing up plans to mine moon water for this very purpose. Shackleton Energy Co. (SEC), for example, hopes to be selling rocket fuel in orbit by 2020, according to its founder Bill Stone.

The good news: It's legal

The good news for outfits such as SEC is that moon-mining operations appear to be legal, experts say.

The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 — which forms the basis of international space law and has been signed by the United States and other major spacefaring nations — prohibits countries from exercising territorial sovereignty over the moon or other celestial bodies. But it doesn't prohibit resource extraction.

"Experienced space lawyers interpret the treaty to allow mining," space-law expert Wayne White, who works in the aerospace industry, told SPACE.com. "I have never seen anybody argue that you couldn't use mineral resources."

White and Nelson both referenced the Moon Treaty of 1979, which sought to set up a regime governing how the moon's resources would be used. The Moon Treaty remains more or less irrelevant today; it has been ratified by just a handful of nations, none of them big players in spaceflight and space exploration.

"If the Moon Treaty wants to regulate how we use natural resources in outer space, then that presumes that it's legal to do so under the Outer Space Treaty," White said.

Nelson compared the legal status of moon mining to that of fishing in the high seas, beyond national borders and claims.

"The idea that you can't claim sovereignty is not necessarily incompatible with the right to go conduct mining operations," Nelson said. "The high seas are not subject to any sovereignty, but people can go and fish there."

The bad news: Title may be ambiguous

While the Outer Space Treaty likely allows mining, it does not set up a system granting explicit title to the extracted resources, according to Nelson. That ambiguity may not cause problems during mining operations, but it could be an issue when companies try to sell the resources.

"If you're pouring billions of dollars into extracting something of value, you don't want the risk that a bunch of people are going to sue you, or boycott you, or sanction you if you take it to market," Nelson said.

White thinks that companies probably can claim ownership, under the Outer Space Treaty, of the ice they mine from a lunar crater. But he agrees that there is a bit of fuzziness — and fuzziness is daunting to big-dollar operations.

"If you really are talking about a multibillion-dollar endeavor, if I were the lawyer for that company, I would say, 'Don't make that investment until we have legislation in place,'" White said.

Comprehensive new legislation should aim to take the ambiguity out, White added.

"Ideally, you'd really need to do property rights, mining law and salvage law all in one package, because some of the elements are common to all three," he said.

Some space entrepreneurs agree that resources on the moon and other celestial bodies won't be used to their full extent unless companies have explicit property rights and title.

"You have to really own the ground upon which you've placed these really valuable facilities," Robert Bigelow, founder of Bigelow Aerospace, told SPACE.com. Bigelow Aerospace is drawing up plans for a quick-deploy lunar base, using the company's expandable space habitats. "You have to instill the ingredients of profit and benefit into the equation."

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter:@michaeldwall.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.